BIO-MIO: The History of Me

The progeny of two Army sergeants, born outside Fort Riley, Kansas one year to the day after the beginning of the Korean War, and seventy-five years to the day after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, I was born into the military and rarely ventured into the civilian world until after I was discharged from my hitch in the Marine Corps in 1972.

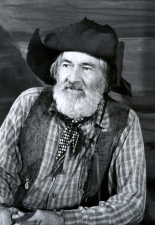

My father was an infantry sergeant who survived the Chosin Reservoir and the Tet Offensive without a scratch. He’s that good. Many guys have asked him how in hell he was able to get through them without getting a Purple Heart. He still snorts derisively. “I didn’t join the goddamn Army to get wounded,” he tells them. He is 85 and is in terrific shape. He left the farm when he was 14 and worked as a laborer and migrant farm worker before joining the Army in 1947. Since he was from southwest Missouri, I guess you could say he was an Okie.

Mom, on the other hand, was of sassy European immigrant stock from Cleveland who, before graduating high school and joining the WACS during World War II, drove a forklift for the Ohio Rubber Company, where they made tank treads. She died in 2010. I still have her Ruptured Duck. My younger sister Leslie also served in the Army and full time with the Army Reserves, and like Dad, drew her pension. She was one of the first two women to graduate from the men’s Army drill instructor school.

When we were kids our parents drug Leslie and me all around the world. I thought it was a gas growing up that way. When I was in the Boy Scouts we hiked the Alps and rubber-rafted the Danube. In August, 1964, after three years in Munich, we had the road-trip-zilla grandest road trip of all time. The auto was a 1959 Ford Fairlane 500, the plane was a C-47, and the train may as well have been the Trans-Siberia Railway.

Dad and I drove the Fairlane from Munich to Bremerhaven to have it shipped back to the U.S. Then we took the slow train home all the way from the North Sea to the Bavarian Alps. When it came time to depart Germany, we rode an Army bus to Frankfurt, where we got into our MATS (Military Air Transport Service) C-47 and prop-washed it to some place in Scotland near the Arctic Circle to refuel, and also to get one of the engines repaired because it was dripping oil. Very cold night on an Army cot under three Army blankets in a Quonset hut.

See how cushy we baby-boomers had it in the Sixties?

Thennn…off we went, into the wild blue yonder from Scotland to Nova Scotia, crossing the Atlantic in an overworked plane from World War II with a hinky motor. But, no problem. Do you know how long it takes to fly from Scotland to Nova Scotia into a headwind in a plane with two propellors? We fueled up again and headed southwest and landed in Fort Dix, New Jersey, and then we took another Army bus to the Brooklyn Naval Yard to pick up the Ford. And here we go…

We drove from NYC to Washington, D.C., and sat on a little hill in Arlington National Cemetery (an old post of ours) while Dad had his orders changed from Fort Polk, Louisiana to Fort Knox, Kentucky.

From Arlington we drove to: Cleveland, Ohio to see my mom’s mom. Remember, this is 1964, we hadn’t even been able to call home in three years. Grandma was one scary old witch, I’ll tell you that. From Cleveland we crossed the country to visit my father’s family, some of it, anyway, in coastal Oregon. Then we drove to Neosho, Missouri, and saw the rest of my dad’s family. Mom was hoping they’d installed indoor plumbing while we were in Europe, because she despised using the outhouse. But they dint.

Then we got to dad’s duty station in Kentucky. We did all this in less than thirty days. In a 1959 Fairlane, an old C-47, and the slowest train in Germany. There was no such thing as auto air conditioning then. There was hardly any air conditioning at all.

It was culture shock to go from Munich to Rineyville, where I spent an absurd couple of weeks in an eighth grade that only had one teacher. Blissfully, we were “on post” pretty quickly. I was educated in schools run by the Department of Defense. In Munich all my teachers were men and all of them were World War II vets. I only had to go to civilian schools for short periods of time, but those times were pretty creepy, though it was easy to give the impression in a civilian school that I was smart.

I went for three years to Fort Knox High School, and then my dad went to Vietnam. We had to move off-post, into a tiny trailer in Radcliff, Kentucky, and I had to finish high school in Elizabethtown, Kentucky, in a civilian high school away from friends I’d had on post. But war has a tendency to break up that old gang of mine when you’re an Army brat. Was I bummed out? I was supposed to be the drum major for the Fort Knox High School Fighting Eagles Marching Band that year. Yeah, but was I BUMMED? Well, no, not really. To survive as an Army brat, you’ve just got to live with those things.

I got out of E-town High as quickly as I could before they expelled me again for not cutting my hair, enrolled at the University of Kentucky, and went to work in a steel mill in Dayton, Ohio. I could try to describe what I did there, but you wouldn’t appreciate the bowels-of-hellish aspect of the place. It was hotter than hell and probably the most dangerous work I ever did, but it paid $3.26 an hour for 48 hours of work a week, and that was a fortune in those days, boys and girls. Then I went to college for awhile, but as much as I wanted a college education, I wasn’t ready to get one yet.

Some of the guys who worked at Duriron were Marines freshly back from Vietnam. And an old “set-up man” told me stories about the Normandy invasion and fighting at the Battle of the Bulge. It made me feel comfortable to hang around with those guys, it was like I was almost among my own. I spent a miserable summer of 1970 in Ashtabula, Ohio, pumping gas into the tanks of Mustangs and Camaros driven by rich college kids. Did I resent that? I resented the crappy job, but I met some interesting people pumping gas into their cars and cleaning their windshields, and a few times I was told by pretty girls driving convertibles that I couldn’t afford them.

By then I’d met the woman I intended to marry (we were 19 at the time), and at the end of that year I joined the Marines.

I went from 195 pounds of mostly blubber, and in a little more than four months later, I was 165 pounds of the meanest, cutest Marine in the Corps. Just look at the pictures. I was adorable! It looks like I’m fourteen years old. I suffered under no delusions, I grew up in the military, I knew what I was in for. I wasn’t in it for love of country, I was in it for a two-year enlistment and the G.I. Bill, which paid my way through college all the way through my masters degree.

I am, of course, a short, soft-bellied galoot with the killer instinct of a Care Bear. Always was and always will be. When I show my old Marine pictures to old Vietnam vets they almost always laugh out loud and ask me how the hell I got through Parris Island with a face like that? I told them I saved a lot of time because I didn’t have to shave. I was carded in liquor stores until my hair turned gray.

Once past a certain point in Marine training the drill instructors start to loosen up, that is, not terrorize you so much, and as you get in shape and prove your proficiency at the rifle range and marching around in precision (“I know a gal who lives on a hill…”) you start to feel pride, and realize critically that you are a part of a team, and that you are far less important than the lives of the men on either side of you. Buddhists and Marines have a lot more in common than you might expect.

And I was grateful for that teamwork. It usually took more than just me to get my fat ass up and over that wall.

After we graduated they put us all in a bus and bused us up to Camp LeJeune, North Carolina, for a couple of months of “ITR,” which stands for “infantry training regiment.” That was when the real fun started. They took away our ten-pound M-14 rifles at Parris Island, and we were issued M16-A1s, the notorious choker of the war in Vietnam. I thought they were shit and I didn’t like them, but they were light, which was a good thing because we had our M-16s, like, on us the whole time were were up there, except when we were doing galley duty. They called that KP in the Army. So in addition to being heavily armed at all times, we got to throw hand grenades and blow shit up with TNT in demolitions training, do infantry maneuvers behind tanks, night fighting, patrols, ambushes, serious trauma first aid training, take-the-beach exercises out of old Higgins boats, and vertical envelopment training out of Huey helicopters, all kinds of fun stuff. Of course they also tear gassed us in a closed up tent and then made us run with a full battle pack and a gas mask on (I got a stomping after that one for cheating and sticking my fingers between my gas mask and my face so I could breathe), and they forced-marched us fifteen miles in full battle gear through ankle-deep sand with only a quart of water, and camp on the fuggin beach. What I remember most is the smell of musty, dusty canvas and kidney shock from bouncing around in the back of a Deuce-and-a-Half driving down dirt roads.

I got to go home for awhile, splendiforous in my summer wool khakis and peaked hat with the big eagle, globe and anchor on the front of it. Phyllis (my future wife Phyllis Unthank, a name which she is thankful she got to lose) and I went to see the musical “Hair,” which I didn’t have much of at the time, but nobody gave me any shit about it. Phyllis and I pledged our respective troths, I guess you could say, and the first thing I did when I got to my final duty station was to put ten dollars down at the B.X. (the P.X. of the Naval Services) and put an $85 engagement ring on layaway.

Years later, when I read Tom Brokaw’s The Greatest Generation, I was surprised to find out that little, squatty, Jewish writer Bud Shulberg had been a Marine in World War II. He served in the South Pacific. His job was supposed to be loading bombs onto airplanes, but he was so bad at it they let him write and publish a newsletter as an alternative to blowing himself up. My kinda Marine. Roy Rogers had Pat Buttram. Hopalong Cassidy had Gabby Hayes. The world is full of beta males. I have a great affinity for tough guys, and I have always been a good wing man. Also, I was good at picking fights in bars where no one would fight my buddies, because they were too mean and ugly and big.

As I like to tell people, then I got a bachelors degree from the University of Kentucky, and then went to the University of Louisville and got an education. I had this simple, naive idea of becoming a teacher – an elementary school teacher. It was a goal that earned me the nickname “Grade School Gerry” in the Marines. (We had a “High School Harry,” too, but they called him that because he was a beach bum.) Phyllis was a nurse “making good bread,” as we said in those days, and I was pulling down G.I. Bill money, and at U of L, federal traineeship money on top of that. We had the time of our lives. We had a hot little red Wankel-engine Mazda station wagon, and we drove that sumbitch everywhere. We did a lot of camping, all over the country.

My first teaching job was in St. Paul, Minnesota, where we created some of the first public school programming for kids with autism in the country. Our son Zachary was born in 1977 “Midway” between Minneapolis and St. Paul. I took up fishing in Minnesota, as an alternative to killing myself in a very windy city riding a 300-pound 1974 Yamaha RD350B motorcycle, which I couldn’t do in the winter, which was from mid-October to the first of May. I wisht I should have kept that job. (And that motorcycle.) I’ve had nothing but mostly bad luck with jobs ever since. I was seriously into backpacking by that time, and spent the summer of 1979 on the Appalachian Trail while Phyllis, bless her, worked at Jewish Hospital in Louisville and lived with her parents until I got back.

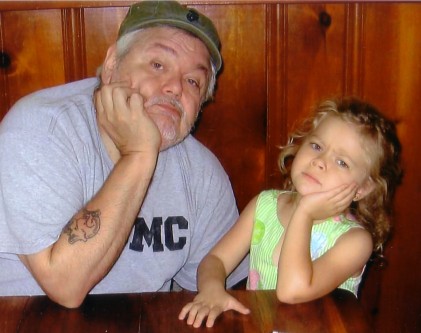

I was 195 pounds of blubber when I hit the trail, and got off weighing 165 – the exact same numbers as Marine training. So twice in my life I have been at my ideal weight, both for about twenty minutes. By then Dad was working for the school system as a maintenance man back at Fort Knox. Long story short, I taught 4th grade for a couple of years for the very same school system that produced me. I also taught in Evansville, Indiana, and back in Louisville, where we came to stay, finally. We were accumulating too much stuff to be moving all over the place, especially with two children. Karly was conceived the night I quit my job at Fort Knox, and she was born eight and one-half months later. Phyllis worked the night before she went into labor, her last night working before her maternity leave started. She was hoping for a week or two of rest before having Karly, but she never even got to take a nap.

So, guess who did Mister Mom duty for the next three years? Best three years of my life.

I taught throughout the Eighties, which is when I also first started making some real money as a writer, teaching GED, substituting for the Louisville public schools, and teaching, for eight delightful years, a night-school course called “Writing for Publication.” Little eight-week continuing education course, five or six students published books, long before I did. Then I got picked up out of a temp agency as a writer for a company in Louisville that published trade association magazines – twenty of them – and they hired me and made me their managing editor. After doing that for three years, I knew that my writing career had taken a wrong turn when the drama of Tieneman Square was unfolding live on CNN, and I was covering the Louisville Home, Flower and Garden Show for Louisville Home Builder magazine.

In 1991 and coinciding almost exactly with the days of the Clinton presidency, I discovered my true calling, which was habilitation case management. During those years I worked for a local comp care agency, helping to set up homes and coordinate community supports and services for people with severe disabilities and mental illness. Eight and a half years. Left because of a case of the red-ass. I was very successful, though, as I was doing the job of a 25 year old woman fresh out of the Kent school, only I was forty-something and a Marine and didn’t give a shit who I pissed off, thus I was able to intimidate the suits at the social services agencies to give me the resources I needed to support my clients in the community. It got to be a pattern. I hopped around from agency to agency, grant to grant, reinventing myself every three years or so, and I got to mess with a great variety of people and populations. I was the lead honcho of the Incarcerated Veterans Transitional Program, the most successful prisoner re-entry program in history (quit because of a case of the red-ass). I also worked with Burmese refugees, stupid kids and homeless people. I finally got fired out of that line of work for giving a case of the red-ass to the wrong people. Client-trumps-employer was my motto, and it caught up with me.

When I was between the comp care and the prison gigs, I taught elementary school at a Hasidic Hebrew day school (trading in on my mom’s mongrel heritage, which also included Italian). I was watching a herd of first graders on the playground one fine September morning when the principal of the school came out and informed me that somebody flew a passenger jet into the World Trade Center.

I felt bad about not volunteering to go to Kosovo back in the Nineties. When they repatriated Kosovo, many families left behind their disabled and mentally ill in Montenegro. I was an expert at supporting the disabled and mentally ill in the community at that time. I could have done some good. So when the Trade Center went down and we went into Afghanistan the following year, I volunteered to go to Pakistan for the summer to help set up schools on the frontier for refugee Afghani children. Didn’t work out, and decided that an intriguing offer to accept my services in Sri Lanka was better than being beheaded elsewhere else in South Asia. The following year I was offered the directorship for English language programming at the U.N. International Children’s Village in Hunan Province, China. And that was also the summer of SARS. Again I got a different but intriguing offer from another foundation in Sri Lanka. And that’s where I spent the summers of 2002 and 2003. Ooooo-WEEEEE-oooo. Cue the theme from The Twilight Zone. It was like I was meant to become a Buddhist.

While living in the jungle under quite primitive conditions, I fell into the laps, or rather at the feet of, some of the most eminent Buddhist monks and theologians in the country. I learned from the study of Buddhism that I was not picking up anything new so much as it confirmed beliefs I can remember always having. Toiling on behalf of other is what my whole life has been about. I volunteered in a hospital full of soldiers wounded in Vietnam when I was in high school. In boot camp I taught a black guy from Louisiana how to read. Teacher. Social worker. I have had the amazing good fortune to marry a woman with a great income who didn’t mind if I disappeared for a month here or a summer there, and who watched me take a series of low-paying jobs that gave me access to people who needed help. It’s always made me happy, helping people out who are in a jam, it is what I have always thrived on. I went to Sri Lanka to teach English, not to study Buddhism. But after only a day in that weird, dirty little country, I burst into tears because I felt I really was around my own people for the first time in my life.

I spent a little time in China, and otherwise have been writing full time since 2011. I have three little grand-daughters and one big step-granddaughter who all look and act like characters from Despicable Me. I take a lot of medications, and do yoga, which has been a real blessing for my health. Also I am a volunteer for Hosparus of Louisville, through which I sit and keep company with dying military veterans. As a Buddhist, I find happiness and satisfaction doing this kind of work. As a Marine, I feel like I am doing my part for the guys who went through hell back in the day. As a writer, I am witnessing the final chapter of World War II.

Buddhism makes you tough. Or it’s supposed to, anyway. Don’t listen to the turtleneck-and-sandals whale-hugger crowd at the meditation center. Old Strib can point your way to enlightenment, and you don’t have to give up beer, fishing or football. I sure as hell didn’t. Retain your testicles while on the path, Grasshopper. You’re gonna need them.

I just finished reading your book and enjoyed it immensely. If you are ever in Albuquerque, let me know and I would enjoy buying you lunch.

LikeLike

You are too kind! And I will. You might like my podcasts, on wisdompubs.org, thesecularbuddhist.org, and the thettooedbuddha.com

LikeLike